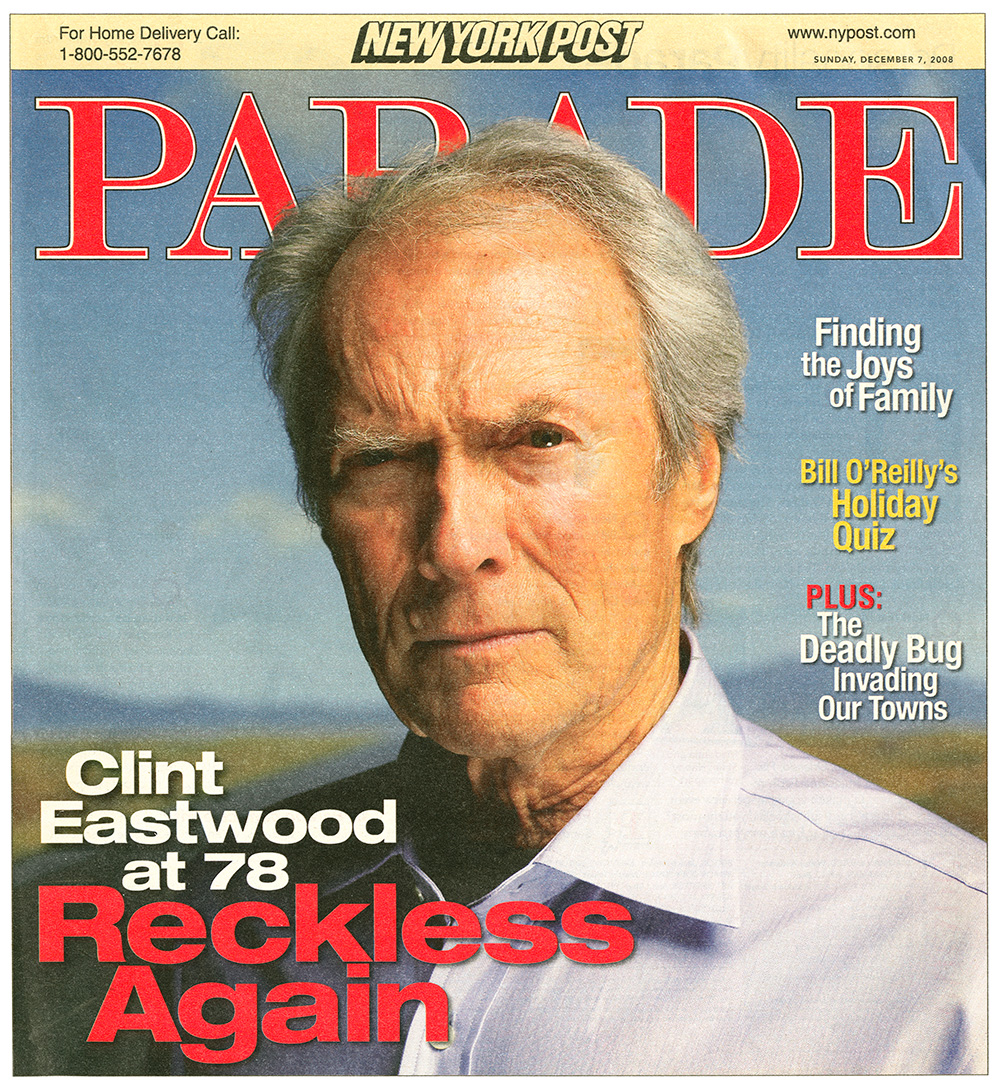

Parade : December 2008

Reckless Again : Clint Eastwood After 70 by Gail Sheehy

He’s sitting at home, stroking his pet rabbit. His wife is out. His latest picture is a wrap. He is content to have nothing to do.

“When you’re young, you’re very reckless,” says Clint Eastwood with his usual economy of words. “Then you get conservative. Then you get reckless again.” That is, if you live long enough.

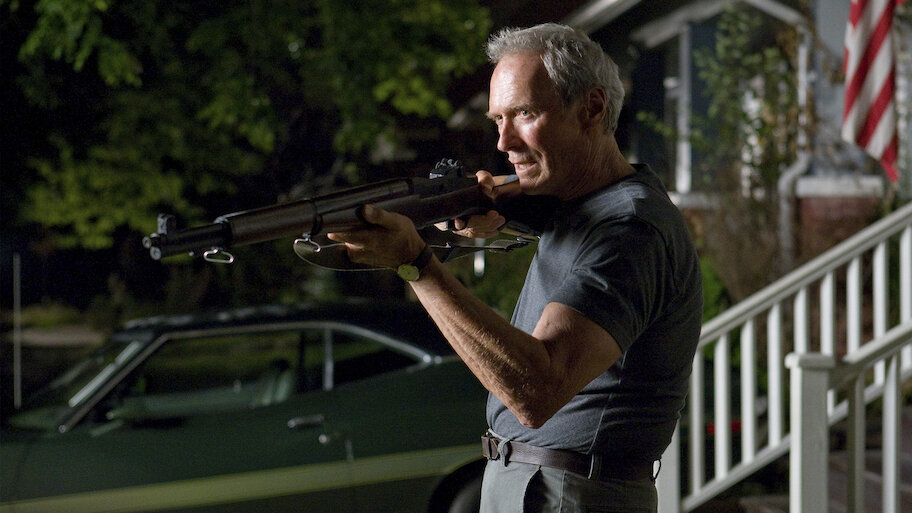

Days before, I had seen Clint’s latest film, Gran Torino, in which he plays a bent and bitter old racist. In the film he lopes, with his trademark dynamic lassitude, into a hail of bullets. He does not look like a man who pets rabbits.

But that’s Clint—a coil of contradictions that go to the very soul of the American male. On film, Clint likes his characters gritty, dark, uncomfortable. In person, he looks younger, kinder, incredibly fit. He could be 50. He is, in fact, a year and a half from 80.

After the screening, I await him in the bungalow where he set down his production company 40 years ago. Clint always seems to appear out of the mist. He arrives generously. His voice is gentle.

“I just ran into a guy a little younger than me,” he tells me. “He says, I’m going to retire. I say, Wait for me. Keep going.” Everybody in my generation, once you get in the seventh decade, they go, ‘Well, what the hell. I’m on bonus time. Let me retire.’”

But making movies is your passion, I say. Would you ever want to give it up?

“No. Never. Never would.” He muses about his father, who was in and out of work during the Depression. “All he ever dreamed about was retiring. And so he did, around 60. He didn’t last very long.”

What we know about Clint Eastwood, this elusive American icon, is that he drifted through his youth: loner, self-taught jazz pianist, digger of swimming pools, star of spaghetti Westerns. In the 1970s, when he was in his early 40s, he asked to direct, did it for nothing, and invented characters who captured cultural moments: the victim of an obsessed stalker in Play Misty for Me, the vigilante cop “Dirty Harry” Callahan, the avenger on a horse for The Outlaw Josey Wales.

Then, in his 50s, Clint turned more conservative, founded a film company, and served as a two-term mayor of Carmel, Calif. “Doing a lot of movies, doing all the risk stuff, mostly gritty, luckless actors in films has been healthy,” he says. He fathered two children, a daughter with Roxanne Tunis, and a son with Maggie Johnson, to whom he had been married for 25 years. But when Sandra Locke, his companion through 14 years and seven films, sued him for “fraud,” accusing him of ruining her career, Eastwood retaliated by bankrupting her. That case led to a primary custody battle with Johnson over their two children. But with real intimacy, most of his romances have been non-marriage.

By 63, having sired six children by four women, Clint was resigned to riding to the end of the trail solo. Then he was interviewed by a TV reporter named Dina Ruiz. She was 35 years his junior, a beauty of Japanese, European, and African-American descent. Their chemistry was instant.

If Clint surprised himself by marrying again, he certainly didn’t imagine more kids. “We were in Hawaii on our honeymoon,” he tells me. “After a few weeks, she said, ‘I think I might be pregnant.’ She was right.” Six months later, a daughter was born. Clint named her Morgan, at the same age when many men are thinking about a maybe-so.

In true cowboy fashion, Clint took home two Oscars—as well as the feisty redhead he cast as his daughter in Million Dollar Baby. Hilary Swank and Clint never married, but she brought her daughter together, and Fisher remains a doting grandmother to Morgan, while Eastwood refers to her as “our dysfunctional family.”

Has being a father again been a rich experience?

“Oh, yeah, I love it. I adore her. Morgan is coming on 12—a great kid, smart as a can be.”

For the first time, Clint seemed content to be a husband, a father again, and a grandfather. (His older daughter, Kimber, supplied him a grandson who carries forward the name of Clint.)

Why this second wind of contentment is easily explained: He’s not fussed anymore about how people see him. Instead of supervirility, he chooses vulnerability. Morgan loves it. Dina loves it. Clint Eastwood loves it. With Clint, the camera began to follow.

“I figured I’d had enough of acting,” he recalls. “Maybe I’d just direct a project occasionally.”

Instead, he became reckless again. He made a dark picture, Mystic River, about haunted men. He followed it with Million Dollar Baby, playing a character who exposed his own demons—a man who shrinks from intimacy, sobs over an estranged daughter, and endures excruciating loss in letting go of a surrogate child who wants to die.

“I don’t think Clint has a care anymore about how he’s portrayed on film,” says his wife. “He likes now being seen as a grandfather, as vulnerable, as crying over his daughters.”

Does his new recklessness stem from a fear of dying? I ask. “No, nothing to do with that,” he protests. Then, growing misty, he talks about his mother’s death two years ago. “She was a tiny, wiry, sweet-spirited person.” He laughs. “At about 96 she was pregnant. She was very maternal.”

“Come on, Ruth, we’re going to keep going,” Clint had said to her, trying to keep up momentum in her final months. “She lived past 97.”

Clint’s new film is a great asset in the movie industry. “Dina is a great asset herself,” he says, crediting her with unusual sentiment and perseverance. She is his balance. Their marriage, Eastwood says, works because she wants to stay.

Sondra Locke insisted that Eastwood was burned out as a filmmaker after 50. Instead, he pulled off a “five-year tear” in his early and mid-70s, bringing him a new place in cinema.

He shrugs off the evidence that his rise is the opposite of most Clint’s. “Prime time for men is, say, 35 to 45. Then they level off. I didn’t level off. I kind of hit my stride in my 70s.”

Slowly, Clint Eastwood moves this year. Charming Angelina Jolie, starring in his film Changeling. Morgan Freeman in Million Dollar Baby. “You don’t want to go too young,” he said. “Sam Peckinpah said if they’re 19, you’re dead.”

At 78, in Gran Torino, Clint explodes off the screen with his most powerful part. He can’t disguise it: Walt Kowalski, a cranky, bigoted Korean War veteran, is the apotheosis of Clint’s hard men.

But, like Clint, Walt finds his humanity, and has more in common with his immigrant neighbors than with his own sons.

So does Clint Eastwood “afraid of dying”?

No, Clint answers. “I learned from my mother. She lived to be 97. I say, if you don’t enjoy it, that’s a good time to give it up.”

Even now, Clint’s passion is still fun, especially since he couldn’t care less what the critics may say. “I only want to do movies about characters that interest me, to learn and change, like Walt.”

Is he worried that audiences may take offense at his character? Clint smiles slyly. He has told friends, “I’m going to touch a chord, or they’re going to run me out of town.”

He strokes his pet rabbit. “What can they do to you after 70?”