The Cable Guide : July 1988

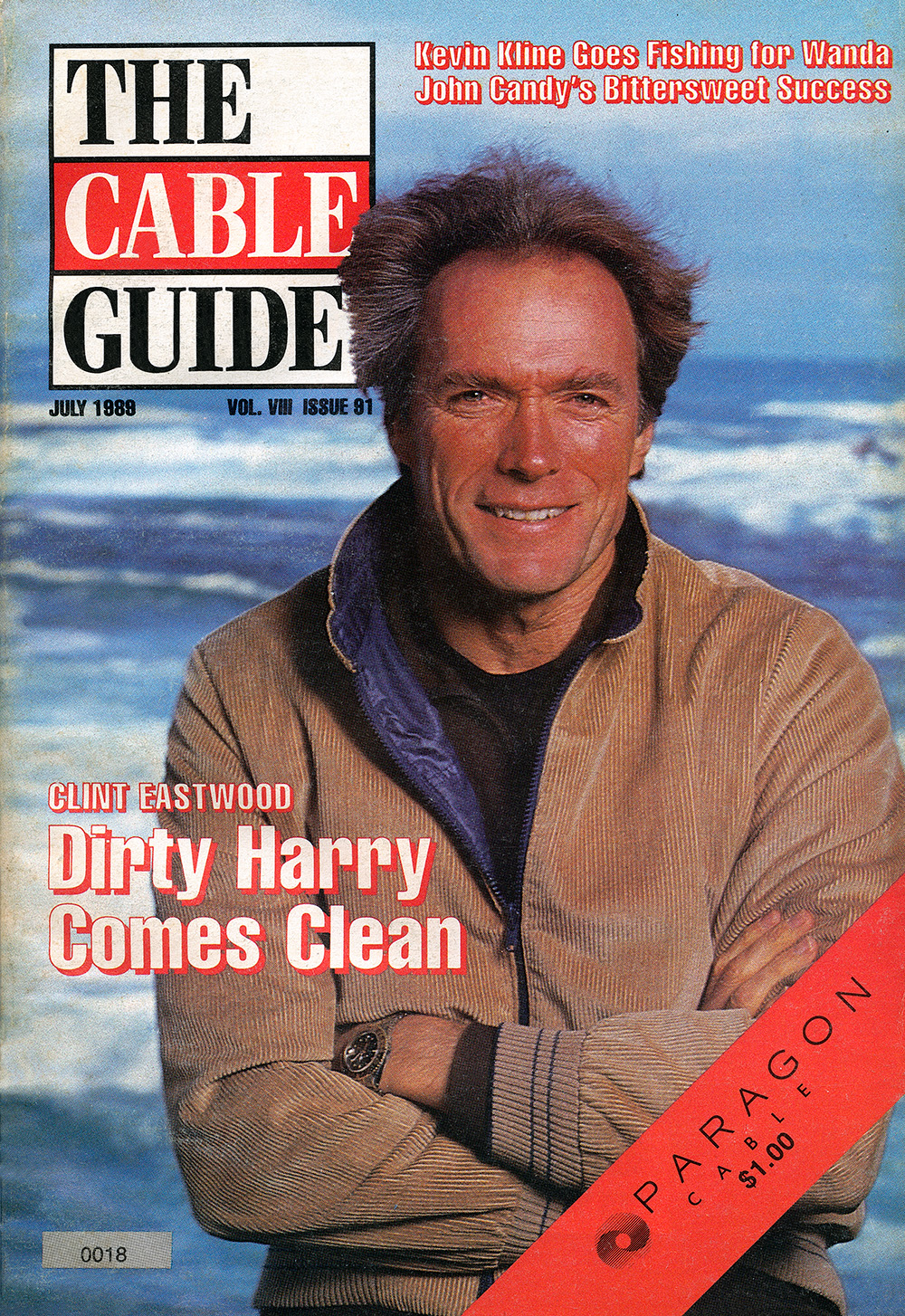

At a corner of the Burbank Studios lot, Clint Eastwood meets you at the door of his Malpaso Productions with an easy smile. None of the intimidating grimace movie tough guys are famous for. In fact, Eastwood in person is friendlier or more hospitable than his image would suggest, and more open, too, about himself, what he takes so seriously. And no one in the business, certainly none of his stature, works harder than he does. In the last year he has released three films — The Dead Pool (which premieres on cable this month), Bird and Pink Cadillac — and has begun work on another, White Hunter, Black Heart, to be photographed this summer in Zimbabwe. Despite his recent breakup with longtime lover and frequent co-star Sondra Locke, he doesn’t appear the worse for wear. At 59, Eastwood looks easily a decade younger, wearing a Dos Equis T-shirt, starched laundry Levi’s and a pair of running shoes. Eastwood relaxes in a nicely appointed but otherwise unpretentious conference room, occasionally resting a leg over the corner of a walnut coffee table. He sipped a glass of cold fruit juice as he nestled in and began discussing his films.

The Dead Pool is your fifth stint as police inspector “Dirty Harry” Callahan. You made the first Dirty Harry in 1971, did you have any idea this enduring and popular character would become mythic?

Not at all. In fact, the first Dirty Harry came to me after a number of other directors and actors had looked at it. I think Frank Sinatra had spent some time developing it. And I think Paul Newman may have considered it. I always wanted to do a detective story, a contemporary kind of thing, and Dirty Harry represented a transition for me from westerns to something else.

What was the initial attraction?

I think the basic romance of the film was that a police officer would extend himself as much as he did. Harry kind of goes overboard. Most of the time you figure, “Well, you’re off duty, the store is closed, you go home and have a beer or something.” But here was this guy who lived alone and was obsessed with following it through. Who believes there’s somebody out there. I think Harry stands for that. He’s an individual fighting the system. He’s trying to get things done.

What makes The Dead Pool different from the previous films?

Harry’s views are pretty much as they always were, but now he’s considered a stalwart, not to be reckoned with, more tolerated. There is a kind of idiosyncratic humor running underneath in Harry’s attitude. In this one, a number of things happen — Harry’s called in to investigate a celebrity death list. One of the names on the list is his own. The story is that Harry can remove himself from the list is to solve the case, apprehend the assailant.

You also did a lot of stunt driving in The Dead Pool. That’s something you quite enjoy, isn’t it?

Yeah, I do enjoy that. In the early days I did it a lot more, but it has become more central to the production you can have problems with insurance companies if you get too involved with the stunts. But in the beginning, when I was still trying to get a foothold on TV as an actor, I might get a small supporting part because I could ride a motorcycle or a horse, drive a car or jump from a building or do some crazy thing.

You did that famous jump from the edge into the moving box in The Gauntlet. And the hanging on the rock face in The Eiger Sanction, was it not?

Yeah, that’s right. The idea was to take a principal cast and a small crew up the mountain and do it for real. Before the film I trained in Yosemite. But the Eiger is cold and it’s sheer and it’s limestone. It’s over 13,000 feet high, almost a perfectly vertical face. I was clinging to a rope in one scene and beside me was another rope down to a safety line. It was at a spot some 4,000 feet up, with no bounce to the bottom. Part of the scene called for me to cut my own rope. I must have checked that safety line a hundred times before I did it. It was the most difficult thing I ever had to do in a picture. You’re out there hanging in space by the safety line with a fellow crew of two or three guys who can’t reach you. You cut it and then you’re just suspended for a moment, way up there. I don’t think I could have done it under casual circumstances, but within the framework of playing character, you do those kinds of things because you need to as them. It’s what the scene requires.

As I understand it, while you were shooting The Dead Pool you were also finishing up Bird, your award-winning film of jazz legend Charlie Parker. It was the second film you directed that you didn’t appear in yourself.

I always wanted to make a film about jazz, because I never thought a really good one had ever been made. Then a couple of years ago the script to Bird came to my attention. It was originally a project for Richard Pryor over at Columbia, but for one reason or another he’d become disassociated with it and the whole project was just in limbo. Later, I got involved with the project. When Ray Stark at Columbia learned that, he asked, “Now how is Clint Eastwood going to play Charlie Parker?”

You were always a big Parker fan.

Oh, yeah. I saw him perform three times when I was a kid. Technically he was innovative and brilliant, and there was great emotion and sensitivity there as well. Once you heard something he did, it was very special. Parker just opened up a whole new world.

Jazz is a true American art form. It represents the freedom Americans dream of, a kind of freedom as idealized through a musical instrument. It questions what kind of freedom Charlie Parker achieved in his personal life. Through a lot of bad habits he destroyed himself. He was also victimized by racism. There were clubs where he was the headliner and he’d have to sit in the back door. But musically he could really express himself with a horn.

In Bird, the depiction of his wife, Chan, as a liberated woman, is one of the most progressive in recent film history.

Well, Chan was a pretty wild cookie. She was just a free spirit who did whatever compelled her. Social priorities and all that didn’t mean much to her. She was a strong individual, and definitely the stronger of the two. And how many girls and women were running off with musicians in those days, especially saxophonists, who kind of hung out on the peripheries? But Chan is really not that much different from the women characters I’ve enjoyed in the films I’ve made. The pictures I liked as a kid often had women in strong roles. Barbara Stanwyck, Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Katharine Hepburn. They all could hold their own with any actor. I think the secret to a well-defined male character is a strong female complement. She could even be the antagonist in some cases. But for that reason alone it’s important that there be balance there. Clark Gable in It Happened One Night is only as effective as the character Claudette Colbert plays.

In my own films, the women I play appear with some character, a little creature, there has to be a draw for me and the audience. I never liked women who were window dressing.

You’ve often described yourself as an introvert when you were young. Wasn’t acting an unlikely profession for you?

Maybe so. I was never much of a ham. But because we were moving a lot, I was often the new boy on the block. I played alone, so I got used to having my imagination as a partner. You create little mythologies in your mind. Acting allows you to get all that out in the open.

Your early career in L.A. was something of a struggle.

Oh, it was. I did all kinds of odd jobs before things started to happen — swimming pools, stuff like that. It wasn’t the most mentally stimulating kind of activity. There were times during the day when I’d drop a shovel or whatever it was and get to a pay phone and call my agent. “Anything new? Anything at all?”

You became an international sensation in the ’60s as the iconic Man with No Name in the trilogy of spaghetti westerns. That’s what gave you the opportunity to establish your own screen persona.

When A Fistful of Dollars came along, it seemed like the kind of role in a western I’d always wanted to play, a guy who just didn’t give a s— and was just very self-motivated. It was a different kind of story that broke a lot of western tradition. But you would have been very surprised to have seen the original script, which was written with just pages of dialogue for the No Name character, where he goes on and on about his past. And I said to Sergio [Leone, the director], “Nobody wants to stop the movie at this point to find out what’s happened before in this guy’s life. Let’s just play the mystery of the character and let the audience fill in what happened in the past.” That was one of the things I experienced very early in life.

What are some of the other roles you have enjoyed?

I’ve always loved character roles, and I’ve always thought of myself as a character actor, never a leading man. The roles I’ve enjoyed most were real characters, as in Dirty Harry, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, Bronco Billy, Honkytonk Man, Kelly’s Heroes, Every Which Way but Loose. Those kinds of films. Cagney and Bogart used to play character leads. They were never too worried about their image. They weren’t afraid of doing crazy things, and they made a lot of great movies in the process. Basically I just like offbeat parts.

The character of Tom Novak, whom you play in Pink Cadillac, is another offbeat kind of guy.

Yeah, he is. Novak’s job is to go out and bail. One of these guys whose living is sort of to ensnare his subjects to get them into court. He might dress up as a radio DJ and call a guy up and say, “You’ve just won your prize!” Sometimes it works. Sometimes it backfires on him. There’s a humorous touch to the film, with a lot of droll situations. It was a good script and fun to play.

In the last decade there seems to have been an evolution in your characters. There’s more vulnerability, a lot of experimentation.

Well, you’ve got to take chances. If I don’t take chances, then I really don’t deserve to be where I am. Because what’s the point of getting into a position to do certain films then not make them? I could go through scripts and say, “No, that’s not commercial,” or “No, that’s not what I built as an image.” But you’ve got to keep stretching yourself into other stuff. There are other things I’ve got to prove in my life too, just to myself as a person, to make comments with other themes and different natures.

With all you’ve done, including a successful term as a politician in your hometown of Carmel, is there anything else you’d really like to do?

Make the next picture, I guess.